· 7 min read

Soft Touches on Clash of Clans Monetization

Sulka Haro

Sulka is a long-time game design veteran. Currently working as a game design consultant, his previous accomplishments includes founding MakieLab, a London-based 3D printed toys and digital games studio, and leading game design at Habbo Hotel. You can find Sulka's blog at http://sulka.net

I’ve met a lot of fellow free-to-play-game developers recently and talking about games always eventually turns to monetization. Talking about monetization inevitably turns to the big successes in the market, including Clash of Clans. I love Clash’s monetization design, as it’s very simple to understand from the player’s perspective. It doesn’t enforce payment at any point and it’s extremely clever in some of the subtle details that I think are driving the urge to spend money. Here are a few of the details I can’t remember reading about and which people sometimes don’t think are as obvious as I thought they were:

First purchase value proposition

Every single player I’ve talked to, purchases an additional builder as the first purchase. Builders are a massively constrained resource in the game and vital for the game pacing once you’ve built the first couple of buildings. Given builders are persistent goods and speed up the gameplay (thus easing much of a player’s frustration), the value proposition of the builder is amazingly good.

This is in big contrast to how most games currently implement persistent goods. For example, King.com has chosen to price the lollipop hammer in Candy Crush as an expensive item aimed at people who are deeply engaged.

The end result of the design choice for Clash is that new players feel they get real value for the gems spent and the subsequent purchases feel much safer, as the persistent value is projected into subsequent purchases. Of course, early in the game the subsequent purchases are also made to build buildings faster, which persist, so the game very effectively teaches you at every turn that you’re making a good long-term investment with your spending.

Keeping the PvP field level in terms of purchases

While you can spend a lot of money buying buildings that allow the construction of better troops, there’s no way to spend money during a fight to your advantage. This, coupled with the player level matching system, which ensures you’re mostly attacking players with similar capabilities, makes purchasing acceptable, regardless of your cultural background. The conventional wisdom for PvP games is that players in the West dislike free-to-play PvP due to perceived unfairness, while players in the East expect spending to affect gameplay in a significant manner.

With Clash, you can spend a considerable amount of money to level up faster, to get cooler troops and to regenerate your troops faster, but because this doesn’t make you win games, there’s both a feeling of becoming more powerful through spending, but also there is no unfairness in any aspect of the game. Effectively, players spend for a higher position in the ranks.

An alternate PvP monetization system that’s used in multiple games focuses on just vanity items, which increase your social status but have no actual effect on gameplay. Clash does this as well, but given the restricted amount of land area available in the villages, this doesn’t scale as well as spending on the expendable currency.

Multi-layer monetization

The core of the game consists of two loops: a building loop for producing and warehousing elixir and gold resources and upgrading production buildings, as well as spending the resources on defences for your village, and a second loop where resources are spent on building troops to attack the other player’s villages to capture resources from them.

During the core gameplay, you are given the option of spending the paid currency to speed up the construction of buildings and you can double the resource production speed temporarily with the paid gems, but the core loop of producing and spending the resources is all done without any need to spend money.

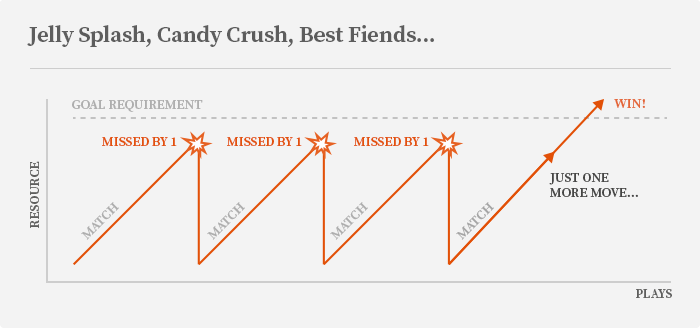

Here lies a very important detail – the game teaches the players to spend significant amounts of the resources produced as part of the core loop, but only the resources you can produce yourself. This feels safe to the player from the monetization perspective, as you’re burning through money you’ve printed yourself. At no point early on in the game does the player feel the core loop is trying to monetise them, in stark contrast to the mechanics at the end of a failed Match 3 game that allows a player to purchase more moves.

The effect of this is that instead of a player feeling they can’t continue to play due to having run out of gems (since they’re not required by the core loop), the player will eventually feel the desire for more elixir and gold and the fact that those are purchasable using the paid gems becomes a payment detail, rather than the player paining over desiring the paid currency. This layer of diversion does wonders to the acceptability of monetization and my assumption is that this greatly increases both the retention and monetization conversion in Clash.

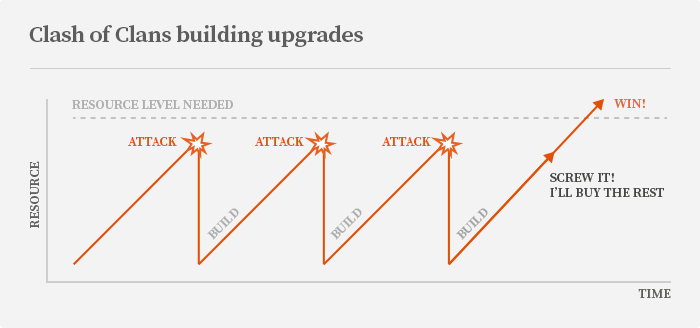

The seesaw, or monetizing the near miss

The resource requirements and building time for improvements increase as you progress through the game. Clash does an excellent job at scaling the cost of using gems for speedups, as covered in this Gamasutra article. So, as you play, you need to wait for longer and longer to get what you want, making spending some cash a little more compelling all the time.

But wait, there’s more! Once the PvP game really starts to hit you, a new pattern emerges. Before you can fill your coffers and start building your improvements, someone comes in and steals your resources! So you build more resources and go steal some from another player, but again, once you’ve almost reached your goal, someone breaks in and gets your goods. So it’s a seesaw – you push yourself up but just before reaching the top, the dude on the other end of the plank pushes you down again. Before long, the player realises that it’s a Really Good Idea to purchase the last 20% of the resource needed before you get attacked.

Psychologically, there is a massive difference between the game preventing you from reaching your goal vs the Clash model of your resources being stolen by another player. As a player, I’m being incentivised to spend due to the other player’s actions, not because the game has a mechanic that enforces payments. And instead of being forced to pay, I’m evaluating the risk and deciding based on the risk evaluation if a purchase makes sense.

Mechanically, this is the same as the near-miss technique used to monetise Match 3 games. In well-tuned Match 3 designs, the levels are typically balanced to maximise the amount of plays where the player gets very close to ending the level, to the point where you feel you are missing the end by just one move. Near misses are addictive (for example, read The Psychology of Near Miss) but also an excellent opportunity to monetise the player by selling more moves. Imagine if casinos sold the ability to move the ball one notch after a spin – not viable for gambling, but perfectly usable in other games.

I would additionally argue that the actual PvP attacks and the related feedback systems in Clash of Clans are balanced in a manner that nearly always leave the attacker thinking that if they’d adjusted the troop deployment just a tiny bit, they’d have done better. Which again plays to the near-miss psychology and probably adds massively to the game’s retention.

Recap

- Persistent goods are excellent tools for improving that first purchase conversion.

- PvP does allow for a design where money gives you power while retaining a level playing field.

- Allowing players the theoretical possibility of playing through the entire game where purchases just provide convenience makes your monetization structure feel great.

- Structures that incentivize spending through player actions are very acceptable from a player perspective, compared to hard spending barriers.

- Near Misses are both addictive, but also a great opportunity to monetize the player.