· 7 min read

Improving your mobile game with narrative (Pt 1)

Chay Hunter

EVP, Marketing at GameAnalytics

What comes to mind when you think about narrative design? You probably imagine Bioshock, Mass Effect or even Stanley Parable – story-driven games where the player’s choices affect the ending. How could you possibly incorporate any of that into a mobile game?

But narrative design isn’t just about branching storylines and giant flowcharts. It can actually be a lot more subtle. Narrative design is about creating a consistent narrative. It’s not just about telling a story, but about showing it in your mechanics, user interface and prompts. It’s the small snippets of audio, item descriptions and visual iconography. Narrative design is about deciding what your story is and making sure that you’re staying consistent with that larger vision.

In this article, we’re going to explain the basics of a good story and then talk about a few ways you can sprinkle memorable moments into your game.

Every story has the three Cs

If you’ve ever done creative writing, you’ll likely come across lots of structures and frameworks for telling a story. For example, it’s worth reading The Seven Basic Plots by Christopher Booker and studying the three-act structure. But there’s a difference between story and plot. Plot is a sequence of events. It’s a way to tell a story.

A story consists of three elements: character, conflict and change. Sure, there are other elements like the world or the themes. But every story – no matter how small – needs these three elements.

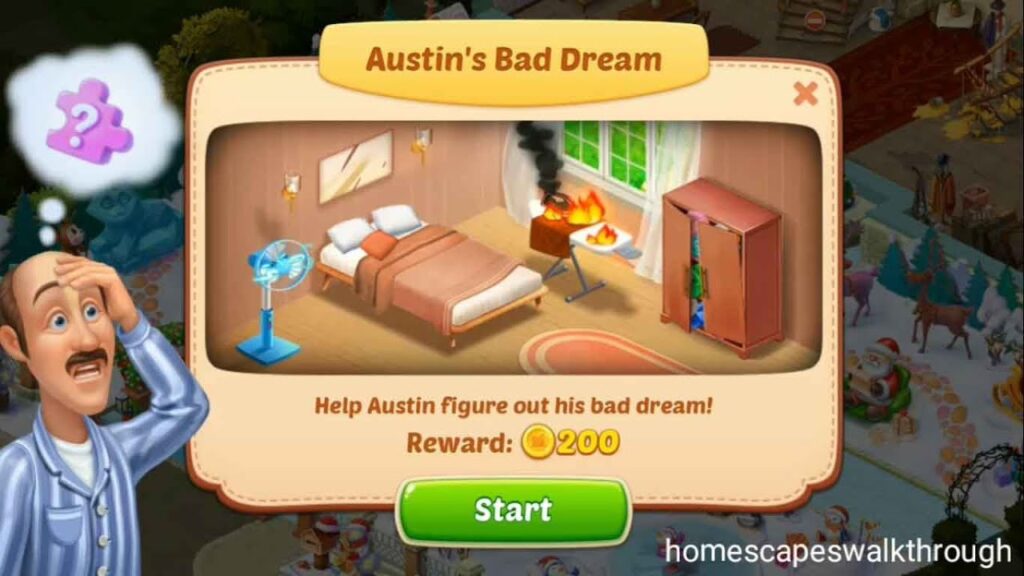

We’re going to use Homescapes as an example. Although it primarily lives in the Puzzle genre, we thought this would be an excellent game to show you how to incorporate characters and stories into your own titles.

1. Character: Who is the story about?

This is a personality – not necessarily a human – that the story revolves around. You don’t need to go into massive depth. Even a faceless blob can have character. All you need is a motivation: What does your character want? What’s their objective?

Image source: Homescapes

This is Austin. He’s a butler who moved back to his parent’s mansion. And he’s trying to renovate their outdated and messy home. Pow, we’ve got a character. If you google ‘Austin Homescapes’, you can even read up on his story on Wiki Fandom – like his friends and family.

Even the Demon Monkey in Temple Run has a backstory. The developers released this video, a day in the life of a Demon Monkey, to give the character more depth.

2. Conflict: What challenges does your character face?

Most games have an obvious danger that comes from the mechanics themselves. If you’ve built an infinite runner, maybe the danger is the boulder that’s chasing the player. In a falling game, it’s the ground.

But danger isn’t the same as conflict. Most stories fall into one of four buckets:

- Man versus man – Two characters directly compete against one another. Two people battle over a piece of land, fight for a romantic partner or squabble over ideological differences.

- Man versus self – The main character struggles with an internal conflict: self-doubt, a moral dilemma or their own tendencies and habits.

- Man versus nature – Your main character is fighting against a beast, monster or force of nature. Maybe it’s the kraken, maybe it’s a hurricane. Either way, the main character can’t reason with their foe. They must defeat, avoid or contain it.

- Man versus society – Rather than fighting a single individual, your character is fighting against a system. For example, they could be fighting against slavery or for human rights.

So what is your story about? Even a simple mobile game can have a conflict at its core. Let’s look at Homescapes. You’re trying to help Austin’s parents have a nicer home. It’s essentially a man versus nature story (well, environment in this case, but it falls under the same bucket).

3. Change: What happens?

Once you have your character and conflict, there’s one last piece to the puzzle. As the story progresses, something needs to change. If nothing changes, it’s not a story. The difference between a normal story and a game is that the player is the one that causes the change. In Homescapes, the player chooses how to redecorate the home (with three different options each time). But it could be anything.

So what changes throughout your story? Does each level represent a new character, performing a similar task to achieve their ending? Or is the player progressing along a path towards a final boss?

Image source: Homescapes

Be aware that you’ll want to make sure your players can replay your game. So are they rescuing multiple universes from the same threat? Or does the threat keep coming back? Or is each level merely keeping the monster at bay – and your character is doomed to endlessly repeat their task?

Use your story to inform your design

Decide on your story using the three principles above. You can always start with your mechanics and work backwards. If you’ve made a game where the player surfs, racing to the finish – ask yourself why the character is surfing. Are they escaping something behind them? Does it represent some inner turmoil, where you’re controlling the good thought and must reach the end before the bad thoughts?

In Temple Run, you’re running away from the infamous Demon Monkeys, after you stole their idol.

Whatever you decide, this can help you change your visuals, the tone of your writing, and even the colour of your menus.

Learn from the best

That’s it for part one. In part two, we’re going to cover different ways to use story in your game, and narrative techniques to layer into your game. But for now, start testing characters in your own game. If you need some more inspiration, here are some of the best characters with backgrounds we’ve seen in games:

- Monument Valley 2 by ustwo Games: A puzzle game with a beautiful story. The aim of this game is to help guide a mother and her child through the valley. The artwork, animations, characters and gameplay all compliment each other. And it’s difficult not to feel an emotional attachment to this game.

- Subway Surfers by Sybo Games: Although they could probably add a bit more story, Sybo games have been consistent with their use of characters across the Subway Surfer portfolio. Jake is at the forefront of these games, alongside his friends Tricky and Fresh.

- Sky: Children of the light by thatgamecompany: This title is all about storytelling. So much so that there are little to no words in the game (you even need to unlock being able to chat with other players). Instead, players rely on visual and audio cues to learn about the world and uncover the story with other players on the server.

- Lily’s Garden by Tactile Games: Similar to Homescapes, this game follows Lily as she renovates her great-aunt’s home. Despite having thousands of levels, the developers have made an effort to keep the story progressing throughout the game (even adding a twist 800 levels in). Tactile Games have done a brilliant job at bringing in interesting characters, conflict, and change throughout the game.

Part two of our narrative series is now out, where we cover the top narrative techniques to make better games. Have a gander through it here. Or if you’d rather get your creative juices flowing, we recently rallied up the top low-budget games that found success through narrative.